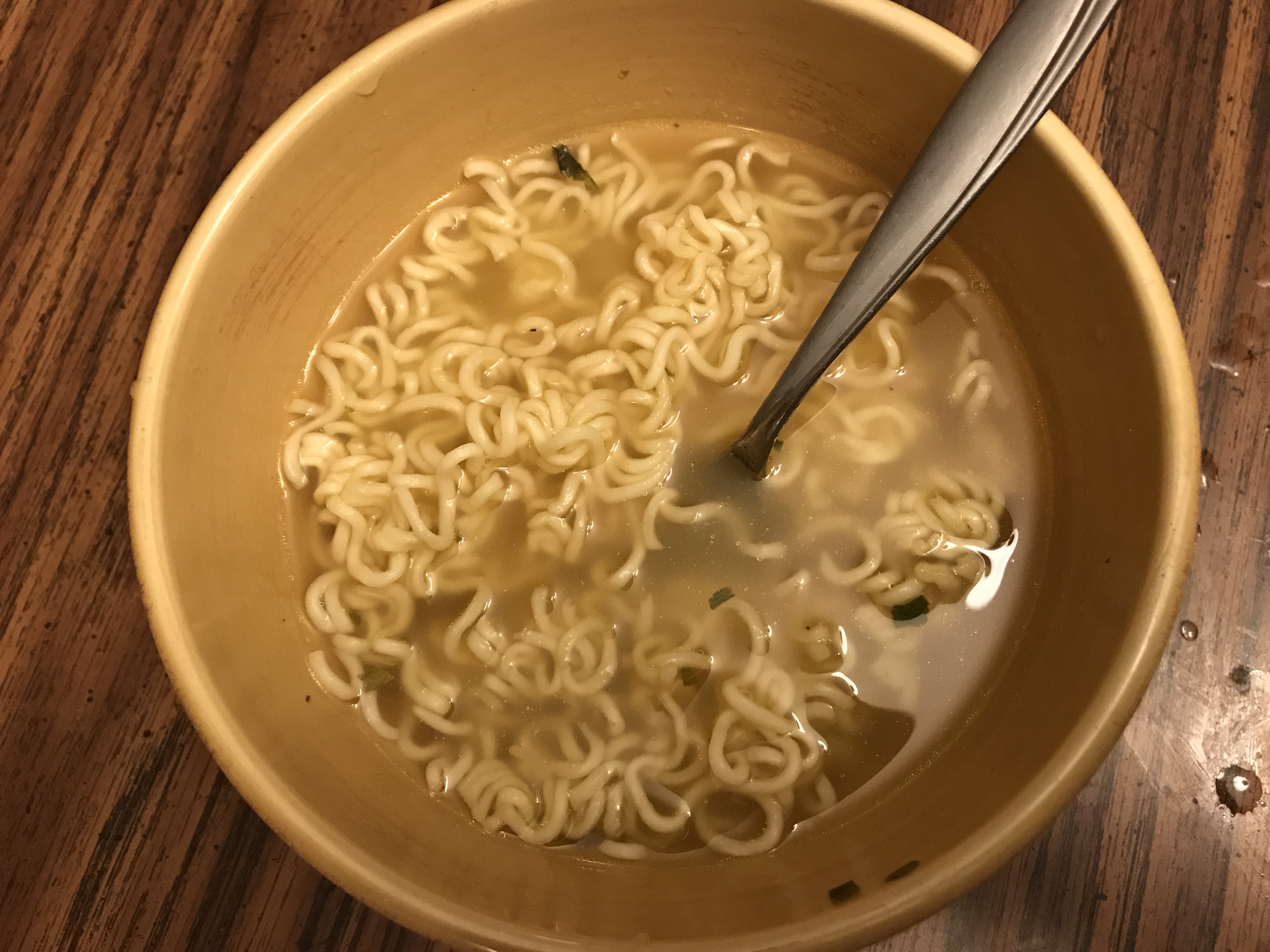

The other day my oldest son had his first packet of ramen noodles. I remember eating these occasionally when I was little and making them in my dorm room through college. When we were houseparents at a group home ramen was an option on Sunday nights when I put the boys in charge of making their own dinner. Even though they had lots of other options, they often picked the ramen, probably because it’s delicious in its own way and probably because it was familiar. In a world of new tastes and scents and sights and sounds and rules and people, ramen pretty much always tastes the same no matter where you are.

As my son started eating it the other night, he was less than impressed. I tried to tell him that our boys loved it and as he was questioning their sanity, I told him that for some of them it was a taste of home in an unfamiliar place. As I tried to explain this to him, I remembered why I hadn’t bought a packet of ramen in over a decade.

It’s because I can’t untangle the memories of those boys from the memories of ramen and the story of one boy in particular.

The boys we worked with saw a counselor regularly. They had lots of opportunities to open up about their pasts and their struggles. In our position, we weren’t encouraged to push for those details or try and get them to disclose anything to us. The assumption was that those moments were best left for the counseling setting. So sometimes we could live with a child for years and not know his full history unless in an unguarded moment he decided to share it. We mostly knew little bits and pieces— fragments of sadness and happy memories of better times. (In retrospect, I wish we would have pushed more. I think a therapeutic relationship with a parent-figure has a lot of power and that power went untapped in a lot of ways because we depended on the counselor to handle these things.)

One night over a bowl of ramen one of our older kids told me for a long time this was all he had to eat at home. He went on to explain that his mom made food for his sibling, but she didn’t want to feed him. He was forced to buy his own food, so ramen was a cheap option. She also wouldn’t allow him to cook it in “her” kitchen or with “her” dishes, so he would make his dinner every night by using the hot water from the bathroom faucet and then would eat in his bedroom by himself. He also had to take his own clothes to the laundromat, which is where he did his homework because he wasn’t allowed to use her washer and drier or her kitchen table to do his work.

I’m not sure what my face did as he told me that story. I remember feeling just dumbfounded about how a mother could do that to her son. I wondered what would have brought her to that point. But there were some things that story made me stop wondering about. I stopped wondering why this young man was so hurt by life, why he was so guarded, why he didn’t want to risk loving anybody. His concept of “mother” was so broken, I could understand why he rejected many of my efforts to love and nurture him.

That story was just the tip of the iceberg of what he experienced, but it has stuck with me in a powerful way. When I see kids who seem resistant to love, I try to imagine what it felt like to be so excluded from your own family that you ate bathroom ramen by yourself every night. What would that tell you about your worth? That young man was extremely capable and competent. He was the model of responsibility, but it wasn’t coming from a healthy place. Sometimes the kids who look the most put-together and adult-like are the ones who are working the hardest to put a bandaid on their own gaping wounds so no one will know. We praise those kids without knowing what’s underneath the surface. We don’t recognize how frantically they’re struggling to never be dependent on another person so they can never be hurt again. We don’t know that this appearance of responsibility comes at a high cost.

Knowing this story has given me more grace with kids and even adults who are struggling, but it has also given me more grace for myself and for other moms who may beat ourselves up about our choices. When you’ve heard these kinds of stories, it makes it a lot harder to get worked up about the mom who feeds her kids a Lunchable instead of the organic nut butter and jam on wholewheat. Even ramen served with love would have done so much to help this boy feel like a person of value. It wasn’t ever about the food, it was about his exclusion from his family. We tend to make our value judgments about the food, the sleeping arrangements, the sports activities, the music they listen to, etc. Those choices all have consequences and we want to be thoughtful, but choices made in real love are rarely going to be abusive or neglectful. When I hear mothers accusing other mothers of “abuse” over bedtime routines, it makes me fairly certain they haven’t been in places to understand what actual abuse and neglect look like. I don’t begrudge them that, but it’s a position I don’t have the luxury of being in.

A child can be raised in love and in poverty. A child can be resilient with the help of a supportive adult. But a child needs more than ramen to survive. It is a joy and a gift to get to be that supportive adult, but it’s rarely easy when a child has been wounded by the people they should have been able to trust.

One Comment

Leave a reply →